|

Battery Hearn

Pre-Invasion photograph: Middleside Barracks, Hospital, Btty. Way, Mile

Long Barracks, NCO Married Qtrs., Cine, Officers Row, Post HQ., Btty.

Wheeler (far right) Light House, Water Towers, Senior Officers Row, Golf

Course, Btty Geary, Btty. Crockett.

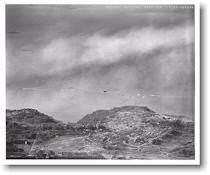

Landing Field B; Officers Swimming Pool;C-47, stick of 7;

Landing Zone A; Mile Long Barracks; Cine; Post HQ, Senior Officers

Residences; C-47 Parachute

Drop; Landing craft; 532nd Engineer Boat & Shore Regiment; USN;

Destroyers; cruiser.

Landing

Zone B; Lighthouse; Water Tanks;C-47 Parachute Drop; stick of 7.

Ciné; BOQ;Post HQ; Lighthouse; Senior Officer's Row; Landing Zone B;

Btry Crockett; |

|

The prospective cost of amphibious assault

was, indeed, one of the chief factors that led to a decision to

use paratroopers. Planners saw the obvious risks in sending

parachute troops against such a small and rough target, but in

view of the GHQ SWPA estimate that the Japanese garrison

numbered only 850 men, the cost of the airborne operation

promised to be less than that involved in an amphibious attack.

Krueger intended to land almost 3,000 troops on Corregidor on 16

February, over 2,000 of them by parachute. Another 1,000 men or

more would come in by parachute or landing craft the next day.

Planners hoped that such preponderant strength, combined with

intensive air and naval bombardment, might render the seizure of

the island nearly bloodless.

An equally important (if not even more

decisive) factor leading to the decision to employ paratroops

was the desire to achieve surprise. GHQ SWPA and Sixth Army

planners hoped that the Japanese on Corregidor would judge that

no one in his right mind would even consider dropping a regiment

of parachutists on such a target. The defenses, the planners

thought, would probably be oriented entirely toward amphibious

attack.

There was only one really suitable dropping

ground on Corregidor, a prewar landing strip, known as Kindley

Field, on the central part of the tail. This area was quite

small and, not having been utilized by the Japanese, badly

overgrown. Nevertheless, Col. George M. Jones, commanding the

503d RCT, recommended that Kindley Field be used as the drop

ground after he had made a personal aerial reconnaissance over

the island. 6 General

Krueger overruled the proposal quickly. A drop at Kindley Field,

he thought, would not place the 'troopers on the key terrain

feature quickly enough, and, worse, the men landing on the

airstrip would be subjected to the same plunging fire that

troops making an amphibious assault would have to face.

The only other possible locations for

dropping paratroopers were a parade ground and a golf course on

Topside, which was otherwise nearly covered by the ruins of

prewar barracks, officers' homes, headquarters buildings, gun

positions, and other artillery installations. The parade ground

provided a drop zone--that is, an area not dotted with damaged

buildings and other obstacles--325 yards long and 250 yards

wide; the sloping golf course landing area was roughly 350 yards

long and 185 yards wide. Both were surrounded by tangled

undergrowth that had sprung up since 1942, by trees shattered

during air and naval bombardments, and by wrecked buildings,

while the open areas were pockmarked by bomb and shell craters

and littered with debris as well. Both fell off sharply at the

edges and, on the west and south, gave way to steep cliffs.

Despite these disadvantages, planners selected the parade ground

and the golf course as the sites for the 503d's drop. The

planners based this decision largely upon the thought that if

the Japanese considered the possibility of a parachute invasion

at all, they certainly would not expect a drop on Topside. 7

In formulating final plans for the drop,

planners had to correlate factors of wind direction and

velocity, the speed and flight direction of the C-47 aircraft

from which the 503d RCT would jump, the optimum height for the

planes during the drop, the time the paratroopers would take to

reach the ground, the 'troopers' drift during their descent, and

the best flight formation for the C-47's. Planners expected an

easterly wind of fifteen to twenty-five miles per hour with

gusts of higher velocity. The direction corresponded roughly to

the long axes of the drop zones, but even so, each C-47 could

not be over the dropping grounds for more than six seconds. With

each man taking a half second to get out of the plane and

another twenty-five seconds to reach the ground from the planned

drop altitude of 400 feet, the wind would cause each paratrooper

to drift about 250 feet westward during his descent. This amount

of drift would leave no more than 100 yards of ground distance

at each drop zone to allow for human error or sharp changes in

the wind's speed or direction.

The 503d RCT and the 317th Troop Carrier

Group--whose C-47's were to transport and drop the

paratroopers--decided to employ a flight pattern providing for

two columns of C-47's, one column over each drop zone. The

direction of flight would have to be from southwest to northeast

because the best line of approach--west to east--would not leave

sufficient room between the two plane columns and would bring

the aircraft more quickly over Manila Bay, increasing the

chances that men would drop into the water or over cliffs. Since

each plane could be over the drop zone only six seconds, each

would have to make two or three passes, dropping a "stick" of

six to eight 'troopers each time. It would be an hour or more

before the 1,000 or so troops of the first airlift would be on

the ground. Then, the C-47's would have to return to Mindoro,

reload, and bring a second lift forward. This second group would

not be on the ground until some five hours after the men of the

first lift had started jumping.

Planners knew that they were violating the

airborne experts' corollary to ground warfare's principal of

mass--that is, to get the maximum force on the ground in the

minimum time. But there was no choice. Terrain and

meteorological conditions played their share in the formulation

of the plan; lack of troop-carrying aircraft and pilots trained

for parachute operations did the rest. The margin of safety was

practically zero, and the hazards were such that planners were

reconciled to accepting a jump casualty rate as high as 20

percent--Colonel Jones estimated that casualties might run as

high as 50 percent. To some extent the casualty rate would

depend upon whether or not the parachute drop took the Japanese

on Corregidor by surprise. And, if air and naval bombardments

had not reduced the Japanese on Topside to near impotency by the

time of the drop, a tragic shambles might ensue.

Planners were also concerned over casualties

during the amphibious phase of the assault, for they realized

that losses could run even higher during landings on the beach

than during the parachute drop. But the planners had several

important

reasons for including the amphibious attack, primary among them

being the difficult problem of aerial resupply and the

impossibility of aerial evacuation. Amphibious assault troops,

planners believed, would probably be able to establish an early

contact with the paratroopers on Topside and thus open an

overwater supply and evacuation route.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|